Floating rate note

Floating rate notes (FRNs) are bonds that have a variable coupon, equal to a money market reference rate, like LIBOR or federal funds rate, plus a spread. The spread is a rate that remains constant. Almost all FRNs have quarterly coupons, i.e. they pay out interest every three months, though counter examples do exist. At the beginning of each coupon period, the coupon is calculated by taking the fixing of the reference rate for that day and adding the spread. A typical coupon would look like 3 months USD LIBOR +0.20%.

Contents |

Issuers

In the U.S., government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) such as the Federal Home Loan Banks, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) are important issuers. In Europe the main issuers are banks.

Variations

Some FRNs have special features such as maximum or minimum coupons, called capped FRNs and floored FRNs. Those with both minimum and maximum coupons are called collared FRNs.

Perpetual FRNs are another form of FRNs that are also called irredeemable or unrated FRNs and are akin to a form of capital.

FRNs can also be obtained synthetically by the combination of a fixed rate bond and an interest rate swap. This combination is known as an Asset Swap.

- Perpetual Notes (PRN)

- Variable Rate Notes (VRN)

- Structured FRN

- Reverse FRN

- Capped FRN

- Floored FRN

- Collared FRN

- Step up recovery FRN (SURF)

- Range/corridor/accrual notes

- Leveraged/Deleveraged FRN

A deleveraged floating-rate note is one bearing a coupon that is the product of the index and a leverage factor, where the leverage factor is between zero and one. A deleveraged floater, which gives the investor decreased exposure to the underlying index, can be replicated by buying a pure FRN and entering into a swap to pay floating and receive fixed, on a notional amount of less than the face value of the FRN.

Deleveraged FRN = Long Pure FRN + Short (1 - Leverage factor) x Swap

A leveraged or super floater gives the investor increased exposure to an underlying index: the leverage factor is always greater than one. Leveraged floaters also require a floor, since the coupon rate can never be negative.

Leveraged FRN = Long Pure FRN + Long (Leverage factor - 1) x Swap + Long (Leverage factor) x Floor

Risk

FRNs carry little interest rate risk. A FRN has a duration close to zero, and its price shows very low sensitivity to changes in market rates. When market rates rise, the expected coupons of the FRN increase in line with the increase in forward rates, which means its price remains constant. Thus, FRNs differ from fixed rate bonds, whose prices decline when market rates rise.

As FRNs are almost immune to interest rate risk, they are considered conservative investments for investors who believe market rates will increase. The risk that remains is credit risk.

Trading

Securities dealers make markets in FRNs. They are traded over-the-counter, instead of on a stock exchange. In Europe, most FRNs are liquid, as the biggest investors are banks. In the US, FRNs are mostly held to maturity, so the markets aren't as liquid. In the wholesale markets, FRNs are typically quoted as a spread over the reference rate.

Example

Suppose a new 5 year FRN pays a coupon of 3 months LIBOR +0.20%, and is issued at par (100.00). If the perception of the credit-worthiness of the issuer goes down, investors will demand a higher interest rate, say LIBOR +0.25%. If a trade is agreed, the price is calculated. In this example, LIBOR +0.25% would be roughly equivalent to a price of 99.75. This can be calculated as par, minus the difference between the coupon and the price that was agreed (0.05%), multiplied by the maturity (5 year).

Simple margin

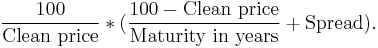

The simple margin is a measure of the return of a FRN.

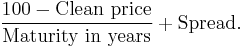

We first compute the "effective spread"

which gives a measure of the "effective spread" over the variable coupon rate. Here the capital gain (or loss) of the FRN is taken into account, and divided over the total number of years until maturity.

The simple margin is calculated as this "effective spread" adjusted for the fact that we buy the FRN at a discount or premium to the nominal value:

See also

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||